//// By: David Petroski ////

Did you hear the news that “…80% of [COVID-19] infections are mild or asymptomatic.” No, that quote is not from a dubious Facebook ad, or a cable news show personality, it’s from the World Health Organization’s Q&A page on the difference between COVID-19 and influenza.

If that is true, how does one screen a caregiver who services those most at risk, like our elderly parents? I am told that many providers (agency or facility) ask a few pertinent questions and/or take the caregiver’s temperature before they start their shift. If no temperature and the questions are all answered in the affirmative, they can don PPE and see care recipients.

Now knowing that the majority of those who are infected may only have only mild or no symptoms, it stands to reason, that it would be prudent to look for other ways to reduce our care-recipient’s exposure from caregivers who pass the current screening protocols, but are part of the 80% “silent spreaders”.

The overall CDC strategy has been to limit the risk of exposure through social distancing, but how do you do that when someone needs daily help with their activities of daily living (ADLs) or memory-care? The answer for some is to reduce the number of new daily contacts that their parents have with a caregiver or caregivers.

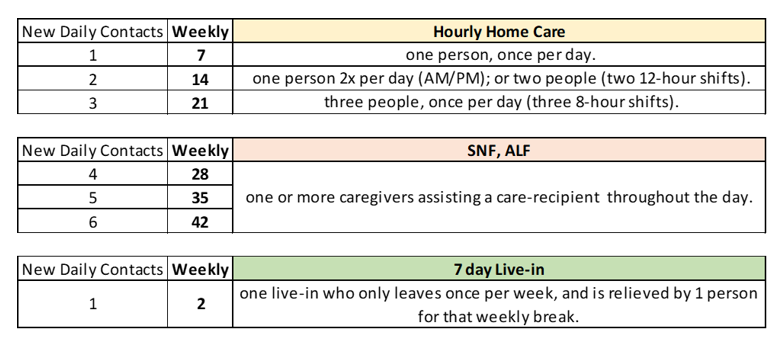

The below chart visualizes the number of times that a caregiver visits a care-recipient after having had contact with other people. It could be in a nursing home, where they go room to room, it could be at an assisted living facility, where they go apartment to apartment, or it could be a home-care aide, going house to house.

Each time they come into contact or recontact (after being in contact with others), they carry the risk of also bringing the Coronavirus with them. Each of these contacts is a Risk of Exposure.

What does that risk of exposure look like for your loved ones, under different scenarios? Let’s take a look.

Of course, the risk of exposure can be reduced by the caregiver properly donning and doffing new PPE each time they enter/exit from doing hands-on care with a care recipient. We all hope that this is done, but as the number of contacts rise, so do the risks of a breach of protocol, especially in situations where PPE is in short supply, and most non-medical caregivers are new to using them correctly.

Of course, the risk of exposure can be reduced by the caregiver properly donning and doffing new PPE each time they enter/exit from doing hands-on care with a care recipient. We all hope that this is done, but as the number of contacts rise, so do the risks of a breach of protocol, especially in situations where PPE is in short supply, and most non-medical caregivers are new to using them correctly.

With live-in care, a screened caregiver can move into a spare guestroom at a parent’s home and help them as needed with their ADLs or memory care, on and off all day. They will even be there overnight if mom (or dad) needs help to the bathroom. Having just one person at home, not multiple aides changing shifts throughout the day or week, cuts down on exposure. Most live-ins will take only one day off a week, and that one day can be covered with one individual, for a total risk of exposure of just 2, versus the alternatives.

Being that the stakes are so high for so many of our parents, it makes sense that you may want to consider speaking to them about the option of using a live-in, even temporarily, to greatly reduce their risk of exposure. It’s simple math.

You can call your local home care agency and see if they can supply you with a live-in that can meet your needs. You can always switch back to hourly aides, or return to the assisted living facility (ALF) when the COVID-19 threat has passed.

To find an Aging Life Care Manager in your parents’ area to discuss your options, go to the Aging Life Care Association® website: www.aginglifecare.org

About the Author: David Petroski is the Founder of Grandma Joan’s Live-in Care Placements. He is a Human Resource Specialist that has helped staff over 10 million dollars in household payroll. David has been an expert panelist for CPE-accredited webinars educating hundreds of senior-care industry professionals about private-hire live-in care. He has been interviewed on radio and is quoted in the 2018 book “Aging With Care”.

WHO reference: https://www.who.int/news-room/q-a-detail/q-a-similarities-and-differences-covid-19-and-influenza