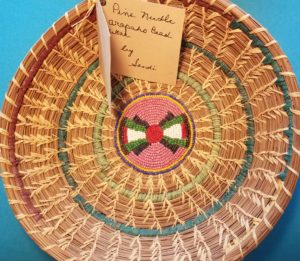

On September 6, 2019, my mother turned 76. As was our birthday tradition, I invited her to lunch and suggested an outing to a local craft store she loved. For the first time ever, she refused to budge from her home. This was new behavior and it really worried me because her world was shrinking. She seemed to prefer solitary activities like beading, knitting, and weaving intricate pine needle baskets, only venturing out when she absolutely had to.

That summer, I informed her that I had been accepted into a Doctor of Social Work program at the University of Southern California and was on a quest to eradicate social isolation, a problem that has been gaining public attention because of its harmful effects on health and well-being. I asked for her assistance on my mission to find answers and spoke to her about how concerned I was about her own situation, which she acknowledged was becoming a problem. A tiny spark of hope suddenly ignited within her at the thought of helping me on my academic journey.

Ten weeks after her birthday she died suddenly and unexpectedly. Her death left me and my siblings shaken to the core. You see, Mom was relatively healthy when she died. The chronic health problems she had were stable. Her diabetes was controlled through exercise and diet. An episode that landed her in the ER in March had been nothing, she said. All diagnostic tests were negative – no stroke or heart attack, and her blood pressure was just fine. Her doctor chalked her dizziness and temporary confusion up to a panic attack and sent her on her way. I was skeptical about the diagnosis but shook off the doubt, preferring instead to embrace the idea that Mom was alright – it was just a false alarm – we had nothing to worry about.

Even though she never finished high school, she owed her own business, and through grit and determination, she raised us six kids, mostly on her own. In her youth, she was vivacious, hard-working, and made friends easily. But as she grew older, her ability to connect with others gradually vanished. At family gatherings, she was grumpy and wanted to return home as soon as her obligations were satisfied.

Mom called me a few times before her death wisely explaining why isolation happens as people age and gave me suggestions about what to do for those caught in the spiral of darkness, she knew all too well. Her observations about her own slide into loneliness dovetailed with all the research findings. Retirement as a hairstylist and closing her salon was a turning point for her, that’s when her all her social connections suddenly evaporated. Vision changes and anxiety caused her to stop driving, limiting where she could go without help. She confided in me about the embarrassment she experienced wearing dentures. Eating with others filled her with so much shame that she purposely avoided social gatherings involving food.

Like many retirees, she said she couldn’t relate to the “old people” who frequented a nearby senior center. When I suggested teaching a class on beading or basket making there, she refused to consider it. Mom had also dealt with panic attacks her entire life and they seemed to worsen as she grew older. The cycle of isolation was self-perpetuating, and she couldn’t seem to find any way out.

Unfortunately, medical providers rarely ask their patients about isolation and loneliness despite the overwhelming evidence linking seclusion to worsening health and early death. In fact, the harmful effects of isolation are so strong that social support is considered a “social determinant of health” – meaning those who are connected live longer and healthier lives than those who aren’t. Researcher Dr. John Cacioppo discovered that loneliness actually changes our brains. That’s why people who are lonely misperceive social cues and have a hard time building relationships. It’s hard to break the cycle once you’re in it.

But if the cycle is interrupted, the benefits of connection are enormous. Older people who regularly interact with others and participate in social activities report better emotional and physical health and have improved cognition. Studies show that those with strong social connections actually require less pain medication after surgery and even recover more quickly. Older people also fall less often, are better nourished and have a lower risk of depression.

It turns out that we don’t need a lot of connections to soften the edges of loneliness. Having a few quality connections that are meaningful and sustained are actually more important than the number of connections someone has.

Answers to the problem of isolation and loneliness will likely be different for each person – there doesn’t seem to be any cookie-cutter approaches that work. Take Mom for example: she had no desire to connect with the older people at the neighborhood senior center, no matter how many nice people she met there. So, we can’t expect that just referring people to places like senior centers or volunteer programs will magically solve the problem. It really comes down to discovering what provides meaning to each individual and then helping make those connections stick. Aging Life Care™ Professionals are particularly well-versed at helping clients enhance wellbeing, rediscover purpose and joy, and make those meaningful, lasting connections.

During this COVID-19 pandemic, we’ve all come to truly appreciate how important our relationships with one another are. While distancing from others protects against the virus, doing so can also make overall health and wellbeing worse. My hope today is that readers take this story about my mother to heart and make time to regularly reach out to people who are isolated. Their lives may depend on you more than you even know. If you feel you or a loved one could benefit from the guidance of an Aging Life Care Expert, visit the Aging Life Care Association website to explore what aging well looks like and to find a professional to help you navigate the journey.

Jullie Gray, DSW(c), MSW, LICSW, CMC, is a trained and licensed as a clinical social worker, she combines over 35 years of experience working in diverse healthcare settings with her passion for working with older adults and their families. Jullie is a principal at Aging Wisdom, an Aging Life Care management and consulting practice serving the Seattle Metro area. She is an award-winning care manager, is the immediate past president of the National Academy of Certified Care Managers and the past president of the Aging Life Care Association. Jullie holds the distinction of Fellow Certified Care Manager. She is currently pursuing her doctorate in social work – focused on eradicating social isolation among older adults.