World Elder Abuse Awareness Day was launched in 2006 on June 15th by the World Health Organization. Elder abuse is one of the most overlooked public health problems in the United States. Victims of abuse are three times more likely than those who weren’t mistreated to die prematurely. Learn how to identify those at risk and what to do if you are concerned about a vulnerable adult.

World Elder Abuse Awareness Day was launched in 2006 on June 15th by the World Health Organization. Elder abuse is one of the most overlooked public health problems in the United States. Victims of abuse are three times more likely than those who weren’t mistreated to die prematurely. Learn how to identify those at risk and what to do if you are concerned about a vulnerable adult.

//// By: Jullie Gray, MSW, LICSW, CMC – Aging Life Care Association™ Member and Fellow of the Leadership Academy ////

Perceptions people have about elder abuse are usually wrong. That’s disheartening because the way we think about elder mistreatment affects our ability to recognize the signs of abuse and our sense of urgency and commitment about stopping it.

Let’s take a look at the most common myths and learn the facts.

Myth #1 – Elder abuse occurs mostly in nursing homes.

Even though elder abuse does occur in nursing homes, it most often happens at home, behind closed doors in every community, regardless of socioeconomic status.[1]

Myth #2 – Strangers and paid caregivers are the ones preying on older people.

It’s heartbreaking, but most vulnerable adults are abused by a known, trusted person – usually a family member. Abuse is frequently cloaked in a shroud of family secrecy that sometimes makes detection very difficult.

Myth #3 – The bad guys always get caught.

Criminal prosecutions of abusers are actually the exception rather than the rule because most victims don’t tell. They’re afraid, embarrassed or simply unable to report any wrongdoing to authorities.

Myth #4 – If there are no bruises or physical signs of abuse, there is nothing to worry about.

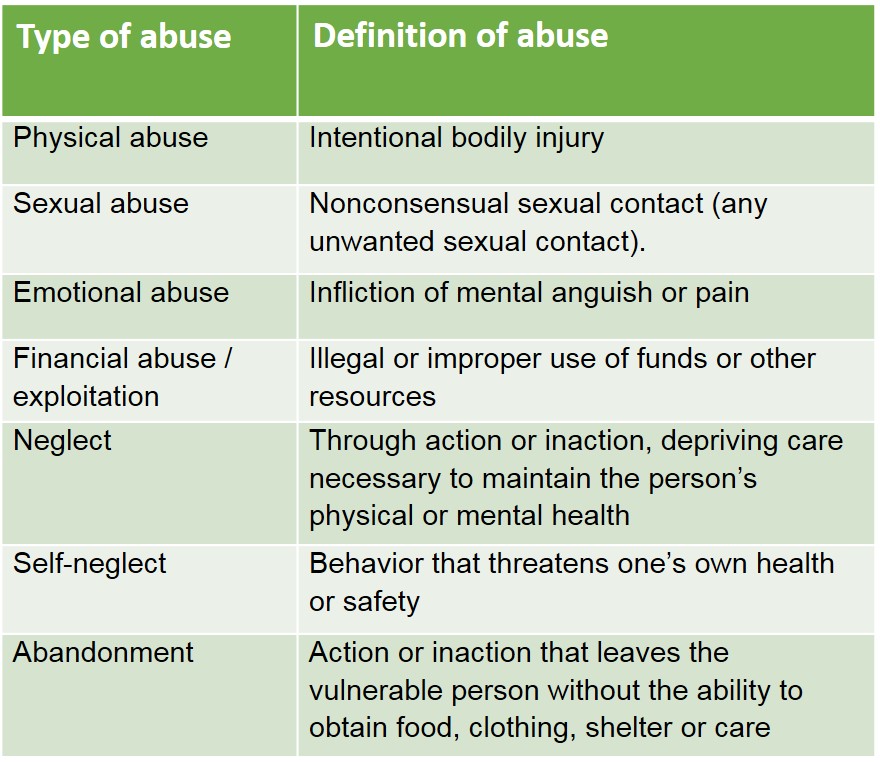

When thinking about abuse, nearly everyone immediately pictures bruises, broken bones and other types of physical cruelty. However, neglect and self-neglect are the most common types of abuse. Emotional abuse and financial exploitation happen frequently too. None of the typical forms of abuse result in obvious outward signs such as black eyes, welts or broken limbs. If you are only looking for the physical signs of abuse you will inadvertently overlook the vast majority of cases.

Myth #5 – Caregiver stress causes elder abuse.

Caregiving by its very nature can be stressful – but stress doesn’t cause elder abuse. Most stressed caregivers do not harm the person they care for. By focusing on caregiver stress as an explanation, we tacitly excuse inexcusable behavior. Using “stress” as a rationale also shifts the focus to the abuser and away from the victim by evoking a perception that if the older person was just easier to care for, not sick, and not so demanding, the abuse would never occur.[2]

Myth #6 – Elder abuse happens to men and women equally.

Elder abuse happens most often to women, but plenty of men fall victim too. Regardless of gender, those with some type of cognitive impairment are at greatest risk of being abused.

Myth #7 – It’s not that big of a deal.

Elder abuse is one of the most overlooked public health hazards in the United States. Victims of abuse are three times more likely than those who weren’t mistreated to die prematurely. The National Center on Elder Abuse[3] estimates that between two to five million elderly Americans experience some form of abuse each year. It is believed that for every one case of elder abuse, neglect, exploitation, or self-neglect reported to authorities, about five more go unreported.

Observing signs of abuse

Since a victim may not be able to report abuse, it’s up to others to observe the signs and intervene.

Physical indicators can suggest abuse is occurring

- Injuries that are inconsistent with the explanation for their cause

- Bruises, welts, cuts, burns

- Dehydration or malnutrition without illness-related cause

Behavioral signs shown by the victim indicating possible abuse

- Fear, anxiety, agitation, anger, depression

- Contradictory statements, implausible explanations for injuries

- Hesitation to talk openly

Patterns seen in caretakers who abuse

- History of substance abuse, mental illness, criminal behavior or family violence

- Anger, indifference, aggressive behavior toward the victim

- Prevents victim from speaking to or seeing visitors

- Flirtation or coyness as possible indicator of inappropriate sexual relationships

- Conflicting accounts of incidents

Signs a vulnerable person is being financially exploited

- Frequent expensive gifts from victim to a caretaker or “new best friend”

- Drafting a new will or power of attorney when the victim seems incapable of drafting legal documents

- Caretaker’s name (or the name of the victim’s “new best friend”) is added to the bank account

- Frequent checks made out to “cash”

- Unusual activity in bank account

- Sudden changes in spending patterns

What to do if you identify someone at risk

We all need to vigilantly look for abuse around every corner of our neighborhood and in the care facilities we visit. One problem, though, is that our culture has taught us to avert our eyes, cover our ears, and mind our own business.

If you are concerned about a vulnerable adult, call 911 or your local adult protective services agency.

Many families also contact Aging Life Care Professionals™ who can provide an unbiased look at the situation, facilitate family meetings to discuss concerns and provide information about care options or ways to approach the situation.

These dedicated professionals understand the laws concerning elder abuse in the state where they practice and can help navigate complicated bureaucracies, act as an advocate for the older person and help develop a safe plan of care. They work hand in hand with adult protective service caseworkers, police departments and elder law attorneys to ensure the safety of the older person and to coordinate appropriate services.

It is human nature to want to put our heads in the sand and change the subject to something more pleasant. But if we identify and report abuse when it occurs, we can stop the cycle and protect our most vulnerable elders.

About the author: A Fellow of the Leadership Academy, Jullie Gray has over 30 years of experience in healthcare and aging. She is a Principal at Aging Wisdom in Seattle, WA. Jullie is the President of the National Academy of Certified Care Managers and the Past President of ALCA. Jullie Serves on the King County Elder Abuse Council in Washington State. Follow her on LinkedIn and Twitter @agingwisdom, or email her at jgray@agingwisdom.com. Aging Wisdom has a presence on Facebook – we invite you to like our page.

[1] https://www.justice.gov/elderjustice/research/

[2] Brandl, B. & Raymond, JA. Generations. American Society on Aging. Fall 2012. Vol 36. No. 3. http://www.ncall.us/sites/ncall.us/files/resources/32_39_Gene_36_3_Brandl_Raymond.pdf